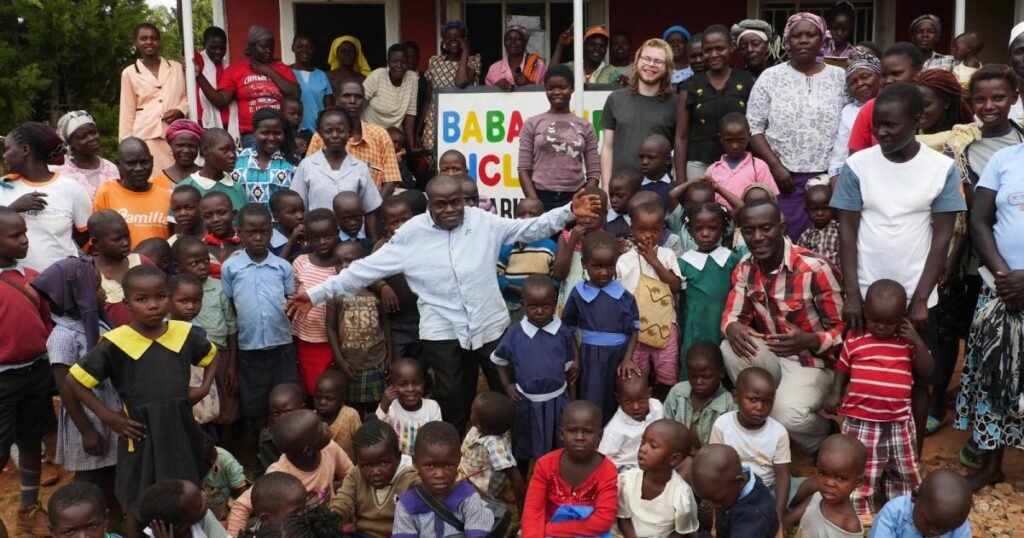

90% of students with disabilities in Kenya do not receive adapted education. A singer has opened an inclusive school in the village of Kabondo to end the stigma.

Baba Gurston would have liked a teacher who understood what it means to run for someone who can't walk. One who would whisper lessons into the ears of those who have trouble hearing. In truth, Baba Gurston would have liked a teacher. He wasn't allowed to go to school until he was ten. "My muscles were too weak to move." A genetic disability hindered his steps: his arms were longer than his legs. That, in a village of farmers who grow corn in the hills overlooking Lake Victoria, in the fertile Kenya that is almost Uganda, is worse than a plague. Worse even than a curse.

“People with disabilities are the most disadvantaged and marginalized group, those who suffer the most discrimination at all levels of society: a complex web of economic and social problems, including gender inequality, create educational, social, and economic barriers. Consequently, a disproportionate number of children and adults with special needs cannot access adequate education and are illiterate,” she summarizes. a report from the Kenyan government itself..

Of the more than 750,000 school-aged youth with disabilities, only 45,000 (61% of the total) are enrolled in school, and only 21% are enrolled in programs tailored to their needs. This means that around 90% of minors with disabilities either remain outside the educational system or attend centers without the capacity to care for them.Beyond the numbers, there are young people like Byron who say goodbye to their siblings every morning before heading off to school. For them, there are no blackboards or English classes, just silent walls that hide them from the world. Being blind, albinism or autism spectrum disorder is a safe passage to marginality. "Families feel stigmatized and are afraid to show their child in public," they say. government experts.

“People with disabilities, especially children, live in hostile environments where their safety is compromised and their future is at risk. They remain marginalized and deprived of opportunities to advance, voiceless as a result of prejudice, violence, and societal abuse,” the government report concludes.

In the four classrooms built where only grass stood two years ago, there is no distinction possible. Here, all students are equal: those with a degraded body or those with blindness. At Baba Gurston's school there is only one motto: Disability is not inability (Disability is not incapacity). “As strange as it may seem, inclusive education primarily benefits children without any type of disability, not only because of all the values it promotes, but also because they learn to feel part of a group, recognizing the abilities within all our disabilities, a key aspect for growing in the workforce by forming teams,” Ramos points out.

“People think people with disabilities don’t have talents, but that’s not true, they do,” Gurston says. At 17, he went to Kibera, one of the largest slums from Africa, the city without a name immortalized by Hollywood in The Constant Gardener. There he met others like him. Artists. By the hand of the Kibera Creative Arts He started a group in which dancers with some kind of disability were the stars. It was his first success. Enough to alleviate a hard life: in Kibera, there are no lives that aren't hard. "For me, the worst thing was the distance I had to walk every day: it was almost an hour and a half, and that's a lot for me," says Baba.

—Why did you decide to come back?

—A friend convinced me. I didn't like the idea of being a teacher, but we started talking about educating young children…

“We don't want children with disabilities to grow up apart, to be told they're special. No one is special! We want them to be like everyone else. The main reason discrimination exists is because we separate ourselves, we hide children, and that generates rejection. If children grow up among their peers, they recognize themselves in each other, they recognize that they too can be seen as different: that's how they become one of the crowd,” she explains. “There's nothing better for fostering a child's development than the support of the class group, children who are aware that we all have difficulties that, with the help of others, become less difficult,” Ramos agrees.

In just one year, the school where everything is learned through music has achieved a lot. There are still challenges: expanding classes, securing a van to pick up children who live farther away, and funding to start a cafeteria, but the first step has been taken. After learning to walk, all you can do is run.

Text adapted by Cristina Oroz Bajo

Fountain: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/07/09/planeta_futuro/1531151350_136446.html